Tuesday, December 30, 2008

Too much of a good thing

However, companies can also try too hard to grow. Hence, it is not that there’s too much growth; there’s no growth at all and that’s precisely because they are trying to hard! Let me explain.

Pretty much everyone attempts to grow. And when we look at different “strategies for growth” – that is, where can growth come from – we usually get presented a list of options: You can diversify, innovate, add new products to your portfolio; partnerships can help you grow, etc. Do these well, and the resulting factor will be growth.

However, what we are often inclined to overlook is that growth in and of itself is simply a lot of work. That is, even when just doing more of the same thing – without adding company partnerships, innovations or diversifying into adjacent businesses – growth taxes a firm’s management capacity. For example, you have to find and manage new customer relationships, add distribution capacity, recruit and train new people and business leaders, develop management systems for a larger organisation and workforce, etc. Growing a firm is a heck of lot of work.

Yet, the options to bring about further growth (innovations, partnerships, etc.) tax your management capacity too. Finding and maintaining new collaborations is a lot of work and requires much attention. So does managing the process of innovation, and developing and commercialising its output. Diversification, internationalization and acquisitions equally are a lot of work; you have to get to know new markets, products and customers; you have to work on integration and a newly formed organisational structure, manage increasingly complex management processes, etc. Doing all of it might just be too much of a good thing.

In a recent research project I evaluated the growth rate of firms in the Chinese pharmaceutical industry. This industry is turbulent and fast-changing, with a lot of entry and exit into the market. There are large potential pay-offs, but the ongoing changes in the country’s economy, population and medical system also make it unpredictable. It’s a market with lots of opportunity for growth, but also quite a brutal one in terms of the uncertainty of how to do this.

I measured to what extent firms in this industry engaged in various strategic vehicles aimed at fostering growth: Diversification into adjacent markets, innovation, establishing partnerships and adding new product lines to one’s portfolio. The results showed that, in isolation, each of these initiatives indeed stimulated growth; yet when used excessively or in combination they actually had a negative impact and hampered a firm’s growth prospects.

Hence, stop trying so hard! You might do better...

Wednesday, December 24, 2008

MEDIA FIRMS INCREASINGLY CHARGED WITH COPYRIGHT VIOLATIONS

That media companies are suing each other is a sure sign of the maturation of online distribution and that money is starting to flow—albeit slowly and at levels far below that of traditional media, which still account for more than two-thirds of all consumer and advertiser expenditures

But the lawsuits really point out the weakness of revenue distribution for use of intellectual property online. In publishing, well-developed systems for trading rights and collecting payments exist. In radio, systems for tracking songs played and ensuring artists, composers, arrangers, and music publishers are compensated are in place and working well. The trading of rights for television broadcasts and mechanisms for payments to owners of the IPRs are well established.

However, effective systems are absent in online distribution and the industry needs to move rapidly to establish them. If the industry can not create such a system on their own, more money will go to lawyers and the rules and systems for online payments will ultimately be imposed by courts or legislators who tire of the governmental costs for solving disputes and enforcing the rights.

Organizations representing print and audio-visual media need to sit down with their major counterparts in online distribution to create a reasonable mechanism by which rights are traded and revenues shared, otherwise they risk imposition of a government imposed compulsory license scheme that will be less desirable to the industry.

Companies that continually argue there should be less government regulation of media operations can’t increasingly go to government to solve their disputes without expecting it to produce more regulation.

Tuesday, December 23, 2008

CEOs and their stock options… (oh please…)

Of course it is to tie a CEO’s pay more closely to the performance of the firm s/he is heading. Inherent in the design of CEO pay packages is the assumption – driven by what is known as “agency theory” – that if you simply put them on a fixed salary, they will be lazy, won’t take any risks and certainly won’t do a thing that will only show up in the company’s results years from now (and hence only benefit their successor). No, these CEO types really need some pay incentives closely tied to the long-term performance of their firms.*

So, we use stock options to tie their rewards to the long-term performance of the firm. However, that could also be done through other means (e.g. shares), right? Correct; we specifically use options to also make these CEO buggers more risk-seeking.

Say what?! (you might think) More risk-seeking? Is that really what we need?! Yes, this agency theory stuff, which determines how we design CEO pay packages, assumes that CEOs are more risk averse than shareholders typically would want them to be. Therefore, in order to stimulate them to take more risks, we reward them through options.*

But what sort of risk-taking does this really lead to? Because what agency theory has not really acknowledged and explored is that there are various types of risk. Some risks may be good; some are not so good… Are we sure these stock options lead to sensible risk-taking?

No I am not so sure. Also because two strategy professors actually measured this stuff: Gerry Sanders from Rice University and Don Hambrick from the Penn State University. They examined 950 American CEOs, their stock options and their risk taking behavior. They found that CEOs with many stock options made much bigger bets; for instance, they would do more and larger acquisitions, bigger capital investments and higher R&D expenditures. That is, where CEOs with few stock options would prefer to invest $50m in a particular project, they would plunge in a $100m.

However, in addition, they would bet (that rather substantial amount of) money on things that had much higher variability. That is, if there was a project that could make them win or lose 20% of the sum invested and another project that could make them win or lose 50%, they would pick the latter; big bets with lots of variance.

Yet, I guess those could still be regarded “good risks”. Gerry and Don, however, also found something else: Option-loaded CEOs delivered significantly more big losses than big gains…! They would more often lose than win the big bets. Surely that is not something anyone would want.

And why is that? Well, through these stock options, you have created individuals at the helm of your firm who only care about upside, but can’t be bothered with the size of the downside; whether they lose 10 million or a 100 million, their stock options are worthless anyway.

And I guess that’s not something even the biggest risk-loving shareholder would applaud. Stock options lead to risk-seeking behaviour, but they’re not always the risks you’d like them to take.

* Although it always makes me wonder whether, even if these incentives would work fine, you would really want a person like that – someone who needs those type of incentives – to be heading up your firm, or whether you then shouldn’t look for someone who would also do the best they can if on a fixed salary...? But anyway; that’s besides my current point.

* Options – the right to buy the company’s shares at a pre-determined price – have large upside potential but very little downside risk; if by the time that the CEO can exercise the option the actual share price is £10 lower than what he can buy the share at, the option is worthless. Yet, it is equally worthless if the actual share price is £50 less. Worthless is worthless (no matter how far the share price has plummeted!). In contrast, if the actual share price is higher than the price at which he is allowed to buy, he makes money. If the share price is £10 higher, he makes 10; if the share price is £50 higher, he makes 50. Thus, stock options are thought to stimulate risk taking; the owner of the option has all the upside but very little downside.

Thursday, December 18, 2008

In a downturn, manage your revenues, not your costs

In prosperous times, companies often fall victim to not being able to resist the many opportunities for growth that present themselves to them. In isolation, many initiatives with respect to new products, new markets or new customers look good but when pursued in combination they have a negative effect and hamper growth. Yet, wealthy firms find all these options difficult to resist precisely because in isolation they look so good. They have the funds to spare and therefore they are inclined to do too much of a good thing.

Andrew Grove, former CEO of Intel, understood this well. Their best-selling product – microprocessors – had endowed them with much cash to spare. However, he resisted temptations to spend it on other initiatives and entering adjacent businesses, telling his people “this is all a distraction; focus on job 1 [microprocessors]”. It made them one of the most successful companies ever.

In a down-turn, companies should look different

However, companies in distress – such as in a downturn – often do the reverse. In academic research, we call this the “threat-rigidity” effect. They focus on their core business, shedding all other things, doing more of what they did before, and which they consider their strongest points, while trying to reduce their cost base to weather the storm, till it all blows over and they can come out of hibernation.

By itself, minimising one’s cost base is never a bad idea (also in prosperous times!) but these companies forget one thing: You have to not only manage your costs; you also need to manage your revenues. And, what’s more, the composition of a revenue base in lean times will have to look different from its composition when times are good. Where in happy times firms are often seduced to spread out too much, while they would be better off focusing on job 1, in meagre times firms are often inclined to focus too much, when diversifying one’s revenue base makes more sense.

Accessing different pockets of revenue

So why does spreading one’s revenue base in meagre times make more sense? It is, among others, because no job will be big enough to sustain the whole firm. What keeps firms afloat is accessing a variety of smaller pockets of revenues. Hence, rather than focus on job 1, hoping it will be enough to sustain the firm, the company’s effort should be aimed at identifying and creating additional sources of revenue. In the downturn, none of these additional sources will be big enough by itself. Moreover, many of these sources would not be attractive in prosperous times, because the firm would not be able to make them grow. However, this is not a time of growth, but of survival.

A diversified revenue base will also reduce dependency and with it risk. In a downturn, the probability of individual sources drying up is large, so a firm can’t afford to be focused on just one or a few of them.

But will searching for additional sources of revenue not be costly? If will not be costless but, by definition, it should not be expensive. Paradoxically, firms should not be focused on winning any big accounts, major new products or customers; they should aim for many smaller ones. They are relatively cheap to access and often the firm will already have knowledge about them; they shunned them in the past considering them too small to advance at the time.

Concurrently, this strategy of exploring multiple smaller pockets of revenue will equip firms well for the economic dawn, which will inevitably come. Their diverse revenue base has laid the foundation for new sources of growth. The firm will be able to quickly benefit from the upheaval in the economy. Many of the smaller pockets of revenue will stay small – and the firm would do well to shed quite a few of them – but the newly formed strategic landscape will be conducive to different sources of revenue than before. Although you can’t tell beforehand which ones it will be, some of the small pockets of revenue will be the new stars on the firm’s firmament.

Monday, December 15, 2008

Mental models – let's all think within the same box

This rigidity-due-to-success effect is partly a mental thing. Once something has brought us much success for a sustained period of time, we sort of forget that there are other ways of doing things. It may even be so bad that we don’t spot the changes in our business environment at all anymore. However, let’s not make the mistake to think that such strong mental models of how we go about doing our business are all bad. They also bring some pretty strong advantages. Consider the following:

Aoccdrnig to rscheearch at an Elingsh uinervtisy, it deosn't mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoetnt tihng is taht the frist and the lsat ltteer are at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a toatl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit a porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae we do not raed ervey lteter by itslef but the wrod as a wlohe.

All of the above is clearly nonsense; they’re not words at all, it is just gibberish. But something makes us able to read it without a problem; that’s because all the right pieces of information are there (all the letters) and roughly in the right shape. Plus, the context (the sentence) makes sense to us. Then, our brain does the rest. We can perfectly understand it precisely because we have seen the individual elements (the words) before and understand the context.

It is the same in business situations; we can quickly grasp and interpret a particular issue if we understand the context and have seen similar problems and situations before. We don’t have to reinvent the wheel every time we see a similar problem but can build on our experience.

Thus, forming mental models is how we learn; they enable us to make quick decisions without the need for complete information. This is a powerful thing to have for every organisation. You don’t want all people thinking out of the box all the time; a coherent group of like-minded people with lots of common experience can be a very useful asset indeed.

The negative effects of common mental models – blindness to changes and viewpoints that don’t fit the model; something known as “groupthink” – you can possibly overcome through smart organisational design. For example, I’ve seen large organisations that created multiple similar sub-units; each of them very coherent, but also very different from each other. They attempt to get the best of both worlds: coherence within units; diversity between them.

Hence, groupthink can be a good thing, as long as you make sure to have multiple groups…

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

“Framing contests”: What really happens in strategy-making meetings

It quickly struck me that there seemed to be a number of pre-formed sub-groups, with their own opinion and agenda. You had the people who wanted to take the company public, those who thought they should diversify into other areas of business, those who thought they should become a “green company”, and so on, and those who thought they shouldn’t care out of a matter of principle.

Of course there were some political motives at play but mostly these people seemed genuinely convinced that their opinion was what was best for the future of the company. And, rather than coming up with new ideas, the strategy meetings seemed to consist of the various people trying to convince each other of their view of the company, its future and the changes required.

Many years later, I read the PhD dissertation work of Sarah Kaplan, a former McKinsey consultant turned Professor at the Wharton Business School. Sarah described such strategy-meetings as “framing contests”. Framing contests, she said, concern “the way actors attempt to transform their personal cognitive frames into predominant collective frames through a series of interactions in the organization”. And although I had to read that sentence a couple of times (before I endeavoured to even begin to believe that I had any clue what the heck she was talking about) it gradually struck me as quite accurate.

In strategy meetings, people try to convince each other by painting a mental image of the future; what would happen if they’d continue as is, and what could happen if they’d follow the course of action proposed by them. They might throw in some numbers based on “research” (put together long after they had made up their mind), and engage in spirited debate, complete with raised voices, rolling eyes and the occasional hand gesture.

And you would win the contest if, through a series of debates, you managed to convince others and get your view of the company and its future adopted as the dominant frame, defining how the organisation sees itself and what it is trying to achieve in the market.

And this may not be a bad way of doing things. I saw the same process unfold – quite successfully – in model train maker Hornby, where the debate centred on divesting, diversifying, investing more or outsourcing production to China (the latter faction won). Similarly, it famously led Intel, over the course of several years, to abandon its memory business in favour of microprocessors.

Former Intel chief executive Andy Grove said about this: “The faction representing the x86 microprocessor business won the debate even though the 386 had not yet become the big revenue generator that it eventually would become”.

Stanford professor Robert Burgelman (who spent a life-time studying Intel), wrote about this same episode: “Some managers sensed that the existing organizational strategy was no longer adequate and that there were competing views about what the new organizational strategy should be. Top management as a group, it seems, was watching how the organization sorted out the conflicting views.”

Later, Andy Grove concurred that that is what happened, and quite deliberately so: “You dance around it a bit, until a wider and wider group in the company becomes clear about it. That’s why continued argument is important. Intel is a very open system. No one is ever told to shut up, but you are asked to come up with better arguments”.

So next time you find yourself debating your company’s strategy and future, realise you’re in a framing contest. Your powers of persuasion will only be as good as your mental imagery.

Sunday, December 7, 2008

Spinning clients – the McKinsey effect

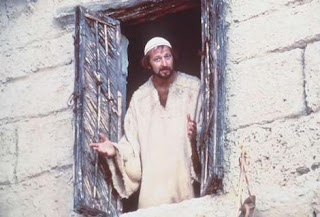

It actually reminded me of a scene in Monty Python’s “Life of Brian”, in which Brian looks out of his window and sees this huge crowd gathered in front of his house waiting for him to speak. And he shouts “you are all different!” After which they dutifully reply in chorus “yes, we are all different”.

[Brian] “You are all individuals!” [Chorus] “Yes! We are all individuals!”

(I particularly like the guy who subsequently says “I’m not”...)

Anyway, McKinsey, like many highly successful individuals and organisations – my great colleague Professor Dominic Houlder tends to call them the most successful religious order since the Jesuits – attracts scorn and admiration in equal measure. And I too believe they do many things right. One of them is that although the average person only stays with McKinsey for barely three years, when you join, you pretty much become a McKinsey person for life. If you "leave", you become an alumnus.

And that is a great feeling to foster if you, as an organisation, lose most of your employees to your customers. Because those people become great advocates for The Firm. McKinsey, for instance, proudly showcases them as alumni (although they have been able to keep remarkably quiet the fact that Enron’s Jeff Skilling was among their most high-rising offspring…). Importantly, what do these alumni do, as soon as they start to work in the real world? Yep, they hire McKinsey consultants…

And these type of beneficial effects do not only accrue to McKinsey; mere mortal organisations can reap them too. Professors Deepak Somaya, Ian Williamson and Natalia Lorinkova, for example, examined the movement of patent attorneys between 123 US law firms and 109 Fortune 500 companies from a variety of industries. Indeed, they found that if one of those Fortune 500 firms recruited a patent attorney from a law firm, subsequently that law firm would start to get significantly more business from that company. And I am sure it works that way for many other types of companies too.

In addition, by the way, Deepak, Ian and Natalia also found the reverse: if the law firm would hire a person from one of the Fortune 500 firms, the business it received from that company tended to go up too! Moreover, if the law firm would poach an attorney from one of its competitors, it would see business go up from the companies that were on the books of that attorney’s previous employer. Apparently, customers often follow a job-hopping attorney to his new law firm.

Therefore, like McKinsey, perhaps you shouldn't be too frightened of people moving. You want to hire people from your competitors and your clients, but you may also want your clients to hire yours. Rather than vilify them for leaving and cut all strings, keep them on the books as alumni, and actively cultivate relationships with them, in the form of clubs, Christmas cards and summer-evening barbeques if necessary! The only thing you don’t want is for your people to move to your competitors… They too may take business with them.

Hence, people will move; if they do, just make sure it is to a (potential) client – that’s the McKinsey way. And, of course, make sure to keep it quiet if they mess it up over there (like alumnus Skilling did at Enron) – that’s also the McKinsey way.

Tuesday, December 2, 2008

Tunnel vision – “in the end, there is only flux”

We know, from running statistics on the performance of companies over time, that especially very successful firms have trouble staying successful, and adapt to changing industry conditions. We call this the “success trap”, “competency traps” or the “Icarus paradox” in business.

But where does it come from? What is causing it? There are various parts to the explanation but one of them pertains to how the top managers of those very successful companies perceive the changes in their business environment.

Research by professors Allen Amason from the University of Georgia and Ann Mooney from the Stevens Institute of Technology, for example, showed that CEOs from firms with relatively high performance were significantly more likely to interpret changes in their business environment as a threat than the CEOs of poorly performing companies, who more often interpreted the changes as a positive thing.

And this is understandable. If you are the top performer in your industry, any change looks like a threat, because things can only get worse; you like things just the way they are, thank you very much! In contrast, if you currently look like a sucker because you're the CEO of a company that is not performing very well at all in comparison to your peers, any change is welcome. It represents an opportunity for things to be altered, and your only way is up.

Allan and Ann also showed that, as a consequence, the top managers of the high performing companies were much less comprehensive in formulating a response to the strategic change; they didn’t spend much time evaluating potential alternative courses of action, they didn’t do much research and analysis, and they sure as hell didn’t seek any outside help or opinion.

Most likely, executives in such a situation are going to try to continue as is, resist the change or minimise its impact. However, if the environmental change is profound, ignoring it is likely not going to work! And this is a problem of all times. In the 1970s, The Swiss watch industry, which was superb at making mechanical watches, invented the quartz watch but they didn’t do anything with it. And when companies from Hong Kong and Japan flooded the market with cheap quartz watches they denied the relevance of the change till they had a near-death experience. Around the same time, tyre maker Firestone responded to the introduction of radial technology by trying to beef up its production of bias tyres (they had a genuine death experience). More recently, traditional newspaper companies fought news-reporting on the internet by suing dot-coms and naively copying and pasting their own paper on a website, while Kodak for a long time tried to ignore digital photography mourning its spectacular margins on photo-film.

I guess you could call it old-fashioned tunnel vision. When your company is hugely successful, you don’t want to see that the world is changing. And if you then, eventually, are forced to incorporate the new technology (or whatever it is that is rocking your world), you try to squeeze it into your own version of reality, rather than accept that reality has changed. But reality is that one day the likes of industry dominants like Google, Intel, or Microsoft will go down. Because as Heraclitus already said some five centuries BC: “In the end, there is only flux, everything gives way”.

Thursday, November 27, 2008

Why aren't there more films like this [sigh...]?

Professor Greta Hsu, from the University of California Davis, examined 949 movies in the US film industry and showed that films that fit more clearly into one specific genre (action, romance, comedy, drama, horror, etc.) generally are appreciated more by the audience. However, films that span various genres attract a larger audience, and that pays off at the box office.

Of course it’s a trade-off – do you go for a broad or a specific set of customers? – and one that most firms in most industries face. It depends very much on the characteristics of the industry where the balance lies; towards specialisation or towards being a generalist.

The fact that in the film industry many firms & films come out as quite general can partly be blamed on the role of marketing. You only really know what a film brings you once you’ve gone to see it (and paid for it). Smart marketers can make multi-genre films appeal to a variety of people, without them realising beforehand that it is going to be a bit of a mish-mash.

For example, the film Cocktail was marketed in four different ways by Touchstone Pictures, including different television commercials, each pertaining to a different genre. Similarly, Miramax produced two different ad campaigns to promote their film The English Patient, one emphasizing the film’s action and war components, and the other one emphasizing the romantic elements of the movie. It turned the film into a product that was purchased by a mass audience.

Altman, in his book Film/Genre, describes this Hollywood strategy as “tell [audiences] nothing about the film, but make sure that everyone can imagine something that will bring them to the theatre”.

Thus, although on average multi-genre films are less appreciated by customers than genre-specific films, it is the former that usually bring in the big audiences, and with it the big bucks. As a consequence, genre-specific films are much more of a rarity, although we love them. Once we see one, we may sigh “why aren’t there more films like this…?” but we really only have ourselves to blame: it is because we do let ourselves be tricked into seeing all this other (multi-genre) crap that it becomes relatively unattractive for film makers to make anything specific.

Tuesday, November 25, 2008

Advice or influence? Why firms ask government officials as directors

It is a bit like we manage our own personal finances – paying bills and filing bank statements etc. In the evening, after a hard day’s work, while watching the X-factor, we quickly glance over the financials and put our signature on the most necessary evils before making a cup of coffee and turning our attention to the newspaper. Bills, bank statements, the accounts of a multinational; what’s the difference really?

But not all outside directors are (ex) CEOs. Quite often, companies also invite ex government officials to serve on their boards. The reasons for that, as research has indicated, are not too hard to fathom: They can provide advice, but they can also provide influence. I guess there’s nothing wrong with buying advice, but the idea of buying influence may be a bit more morally challenged…

Government officials can provide specific advice on how to deal with government-related issues. They have specific knowledge and experiences and can therefore provide valuable advice. But ex officials can also offer contacts for communication which are not accessible to other companies. Then, directorships start to become the currency used to buy influence, which makes it a bit more dubious. It certainly gets dubious if they provide for a direct way to influence political decisions. Some people have even suggested that board memberships for ex government officials are rewards for “services” rendered while they were in government… which would certainly be in the “barely legal” category.

It’s hard to examine which of the aforementioned reasons motivate firms to invite ex government officials onto their board. However, by analysing exactly which individuals get offered the job, we can get a bit of a sense of what’s going on. Professor Richard Lester from Texas A&M University and some his colleagues analysed this question – which government officials are most likely to be approached to serve on a board? – using data from the United States. They tracked all senators, congressmen and presidential cabinet ministers who left office between 1988 and 2003 and figured out which of them got offered directorships.

They found that the longer officials had served in government, the more likely they were to be approached for a directorship. I guess that could be because more experience gives them more influence but also because experience made them better advisors. Presidential cabinet ministers were more likely to receive board invites than senators, who were more likely to be approached than congressmen. I think this starts to lean towards an “influence” explanation for board invites rather than an “advice” one, but I guess one could still argue that cabinet ministers are simply the better advisors.

However, another clear finding was that these people would either get asked for a board very shortly after leaving their government position or not at all. Senators and former cabinet officers would usually be snapped up in the first year after leaving office. This could hardly be because after a year they all of a sudden would make for lousy advisors; it’s much more consistent with the fact that their ability to influence government decisions quickly deteriorates after leaving office. And it seems consistent with the idea that they get offered the job in return for services already delivered…

Finally, Richard and colleagues examined what happened in the case of a government change; that is, if the party in power (in the House, the Senate, or the White House) shifted from Democrat to Republican or vice versa. The effect of this was clear; the ex government official, associated with the party no longer in power, would lose much of his attraction as a potential board member. Because if the wrong party comes to power, you just lost much of your power to influence and with it your value as a potential board member. Clearly this points at an “influence” argument; companies ask ex government officials on their boards to bend political decisions in their favour. And I'm afraid this puts these officials firmly in the barely legal category.

Thursday, November 20, 2008

How to tame an analyst

That is of course a nice, glamorous perk for the average analyst; being invited to personal audiences with a real-life CEO. Mind you though, if you subsequently don’t write nicely about their company, they won’t invite you back! That’ll teach you!

Or do you think I am exaggerating now, and really starting to create a gimmicky parody of what really is a very serious financial business? Well, let me tell you a story. And it is a story about facts.

Professor Jim Westphal from the University of Michigan and Michael Clement from the University of Texas Austin examined exactly this issue: the relationship between CEOs and analysts. They surveyed a total of 4595 American analysts and examined the strategies and performance of the companies they made recommendations on.

In the surveys, they asked the analysts to what extent they had been given the privilege of personal access to certain top executives, in the form of private meetings, returned phone calls or conference calls, and so on. And how often this form of individual access was denied. They also asked them about personal favours that these CEOs might have done for them, such as putting them in contact with the manager of another company, recommending them for a position or giving advice on personal or career matters. Then Jim and Mike ran some numbers.

First of all, their statistical models showed that the CEOs of companies that had to announce relatively low corporate earnings started to significantly increase the number of favours they handed out to analysts, by granting them personal meetings, jovially returning their phone calls and making some much-appreciated introductions. Similarly, CEOs of companies that were about to engage in diversifying acquisitions – a rather controversial if not dubious strategy that the stock market invariably hates – engaged in much the same thing. Clearly, these CEOs were trying to sweet-talk the analysts and mellow the mood ahead of some rather disappointing announcements they were about to make. The question is: did it work…?

What do you think? Is the pope catholic? Is Steve Jobs whizzier than MacGyver? Did Neutron Jack eat all his meat?! Is Bill Clinton heterosexual…?!?! Sorry, let me not get carried away in analogy here, the answer is yes.

Of course it’s yes. It works. Analysts who received more personal favours from a CEO would rate a company’s stock more positively when he announced disappointing results or engaged in questionable strategies. And if they didn’t? Yep, you guessed it: those analysts who in spite of the favours had the indignity of downgrading the company’s stock all of a sudden ceased to see their phone calls returned, would be denied any further personal meetings and sure as hell were not given the phone number of the CEO’s golfing buddies. And the only remaining advice they ever received was to get a life and bend their bodies in ways that would enable self-fertilisation.

And this worked too. Not the self-fertilisation but the social punishment of the degrading analyst; other analysts aware of their colleagues' loss of status would be significantly influenced by their plight when making their own recommendations: they made sure not to follow them into the social abyss and were unlikely to downgrade the firm of such a CEO.

Thus, sweet-talking works. But mostly if followed by a good dose of old-fashioned bullying.

Sunday, November 16, 2008

What really caused the 2008 banking crisis?

One central element in each of these disasters, including the banking crisis, is caused by the division of labour and specialisation within and across organisations. In the case of investment banks, financial engineers drew up increasingly complex financial instruments that, among others, incorporated assets based on the American housing market. Yet, the financial engineers didn’t quite understand the situation in the housing market, the people in divisions and banks participating in the instruments didn’t quite understand the financial constructions or the American housing market, and when it all added up to the level of departments, groups, divisions and whole corporations, top managers certainly had no clue what they were exposed to and in what degree.

Similarly, in Enron, managers did not quite understand what its energy traders were up to, Ahold’s executives had long lost track of the dealings of its various subsidiaries scattered all over the world, and also Union Carbide’s administrators had little knowledge of the workings of the chemical plant in faraway Bhopal. The complexity of the organisation, both within and across participating corporations, had outgrown any individual’s comprehension and surpassed the capacity of any of the traditional control systems in place.

Another crucial role was played by the myopia of success. Initially, the approach used by the companies involved was limited and careful, while there were often countervailing voices that expressed doubts and hesitation when gradually less care was taken – there certainly is evidence of all of this in the case of Enron, Ahold and also Union Carbide. However, when things started to work and bring in financial returns, as in the case of the banks, the usage of the instruments increased, sometimes dramatically, and they became bolder and more far-reaching. Iconoclasts and countervailing voices were dismissed or ceased to be raised at all. For example, in Ahold and Enron, the financial success of the firms’ approaches suppressed all hesitation towards their business strategies.

Another crucial role was played by the myopia of success. Initially, the approach used by the companies involved was limited and careful, while there were often countervailing voices that expressed doubts and hesitation when gradually less care was taken – there certainly is evidence of all of this in the case of Enron, Ahold and also Union Carbide. However, when things started to work and bring in financial returns, as in the case of the banks, the usage of the instruments increased, sometimes dramatically, and they became bolder and more far-reaching. Iconoclasts and countervailing voices were dismissed or ceased to be raised at all. For example, in Ahold and Enron, the financial success of the firms’ approaches suppressed all hesitation towards their business strategies.This caused a third element to emerge: it actually became improper not to follow the approach that brought so much success to many. In the case of investment banks, other banks and financial institutions that did not participate to the same extent as others, received criticism for being “too conservative” and “old-fashioned”. Investors, analysts and other stakeholders joined in the criticism, and watchdogs and other regulatory institutions came under increasing pressure to get out of the way and not hamper innovation and progress.

Similarly, Enron was hailed as an example of the modern way of doing business, while analysts (whose investment banks were greatly profiteering from Enron’s success) recommended “buy” till days before its fall. Similarly, Ahold’s CEO Cees van der Hoeven continued to receive awards when the company had already started its freefall. All of these organisations’ courses of action had been further spurned and turned into an irreversible trend by the various parties and stakeholders in its business environment.

This relates to a fourth management factor that contributes to the formation of a crisis. It’s the factor that is related to what was on everyone’s lips in the immediate aftermath of each of the aforementioned crises: greed. Somehow, all organisations and individuals involved seemed to have let short-term financial gain prevail over common sense and good stewardship. But in all these cases, greed was not restricted to the few top managers who ended up in jail or covered in tar and feathers. Ahold’s shareholders initially profited as much as its executives. Investors, politicians and even customers shared in equal measures the early windfalls of Enron; likewise for the investments banks. Even the Church of England made big bucks on the financial practices they so heavily criticized in the days following the collapse of the system.

The greed factor, however, does not stand alone; it is built into the structure of the whole corporate system. Traders are incentivised to concentrate on making money; top managers are supposed to cater to the financial needs of shareholders above anything else – opening themselves up to severe criticism if they don’t – and customers are expected to choose the best deal in town without having to worry where and how the gains were created. However, none of these parties actually see what lies behind the financial benefits, and where they come from. The traders just see the numbers, the investors only see their dividends and earnings per share and the Church of England simply chose the best deal while the archbishops were unaware it amounted to short-selling. The high degree of specialisation and division of labour both within and between the financial institutions may have revealed the result of the process but showed no sign of how these profits were actually produced.

All these things point to one underlying cause: the structural failure of management. The management systems used to govern these organisations were unable to control the inevitable process towards destruction. Whether analysing Enron, Ahold, Union Carbide in 1984 or banks in 2008, the striking commonality is the sheer inevitability of the disaster; each of them were accidents waiting to happen, given the state of the organisation.

More rules and regulations and more quantitative and financial controls are unlikely to solve the problem, and prevent similar events from happening in the future. All organisations and people involved in these cases, ranging from top managers to traders and customers, were governed and incentivised by means of quantitative and financial controls. However, today’s businesses are too complex to be controlled by rules and financial systems alone.

Instead, organisations will need to tap into the fundamental human inclination to belong to a community (such as an organisation), including people’s desire to do things for the benefit of that community rather than focus on their individual, narrow interests. These are alien concepts in the City today, where incentives are geared towards optimising individual, short-term performance while company loyalty and a sense of community are all but destroyed by the financial incentives and culture in place. Yet, when such human desires to contribute to a community are artificially suppressed through narrow financial incentivation schemes, weird things can happen – and the 2008 banking crisis certainly was one weird thing.

Tuesday, November 11, 2008

Too hot to handle: Explaining excessive top management remuneration

First of all, there has been quite a bit of research that has tried to show that CEO compensation is tied to firm performance. It ain’t. That research has tried, has tried hard and harder, but just could not deliver much evidence that CEO remuneration is determined by firm performance. Admittedly, some studies have uncovered some minor positive relations between pay and performance but it wasn’t much.

The only economic factor that has delivered some consistent results worth mentioning – indicating a positive influence on CEO pay – is firm size: bigger firms pay better. Although this may be an intuitive result, it is actually not that clear why... Why do the CEOs of big firms earn more? Do CEOs of big firms put in more hours? Not that I know. Is managing a firm with 100,000 employees that much harder and more demanding than managing a firm with a tenth of that number on their payroll? Not necessarily. So what is it? I guess one could argue that a top manager of a large firm can do more damage if he messes it up and, since large firms generally have more resources available than smaller firms, they hire (and pay) the best. Yeah... I guess that could be it... Although research has also shown that, on average, large firms are not really more profitable than small ones, so I am not sure these better paid guys actually are better at their jobs. But anyway, we have found one thing that seems to explain top executive pay, so let’s not be too critical about it but accept it with grace.

But, beyond plain size, what then does determine CEO remuneration? Well, let’s start with who determines CEO compensation. In most counties, for public firms, that’ll be the board of directors. And, specifically, the directors that serve on the firm’s remuneration committee (usually 3-5 outside directors). And, yes, there has been some research on these bozos.

Three professors who did research on the relation between CEO compensation and boards of directors were Charles O’Reilly and Graef Crystal from the University of California in Berkeley and Brian Main from the University of St. Andrews. They studied 105 large American companies and first computed the relation between a bunch of economic factors (such as firm performance and firm size) and CEO remuneration. The only thing they found was a connection between company sales and CEO pay. In short, on average, if a firm’s sales increased by $100 million during the CEO’s tenure, his salary would go up by $18,000. That’s hardly impressive, now is it...?

Then, Charles, Graef and Brian did something a bit more interesting. You have to realise that the directors on these committees are usually CEOs or ex-CEOs themselves. Therefore, Charles and his colleagues compared the salaries of these director CEOs to the salaries of the CEOs of the companies for which they served on the remuneration committee. There was a strong relationship between them. An increment in the average salary of such an outside director with, say, $100,000 was associated with a jump in salary of $51,000 for the CEO, after statistically correcting for all the results due to the effects of firm size, profitability, etc.!

Charles, Graef and Brian argued that this association could only be the result of some sort of psychological social comparison process. The directors on the remuneration committee who decide on the CEO’s salary simply determine this guy’s pay by looking at what they themselves make at their companies. And thus, doing this, they don’t feel hindered at all by irrelevant issues such as the firm’s actual performance during the tenure of the CEO or any other silly things like it!

And guess what, who do you think determines who gets asked to serve as an outside director for a firm...? Any guesses...? Yep, it’s usually a company’s CEO who generally nominates new outside directors. That does make it rather tempting for a CEO to be rather selective about which peers you nominate to serve as director and determine your compensation packages, doesn’t it...? Since, according to Charles, Graef and Brian’s research, their wealth may nicely domino into your bank account. The last people you want on your board are those guys who are on a meagre package themselves; because they would likely curb your dosh as well. Instead, bring in the rich guys; they’ll make you rich too!

Friday, November 7, 2008

Deciding stuff – that’s the easy bit

The three things that these senior executives said were the most important issues in their view and experience were:

1. Attract and retain talent

2. Decide on the company’s next avenues of growth

3. Align the organisation towards one common goal

Some further (statistical) analysis showed us that the number one – “attract and retain talent” – pertained to things such as putting together an effective top management team, and managing top management succession. Many business leaders see as their main task to recruit and develop other leaders, and it seems our senior executives were no exception.

The second one – “decide on the company’s next avenues of growth” – reminded me of a survey one of the global consulting firms used to run (I believe it was the then Anderson people). They ran an annual survey asking CEOs “what keeps you awake at night?” It was one of these PR endeavours aimed at getting some free publicity in the business press, bolstering their image as a source of management knowledge & wisdom. However, this survey was not a great success, and they seized to run it, simply because every year the same thing came out on top (which made it rather boring and hardly ideal to get the business press excited…) and that was: “The firm’s next avenue of growth”. Our survey confirmed this result.

The third one – “aligning the organisation towards one common goal” – pertained to this thing that tends to make non-senior executives (including business school professors) smirk: creating a mission and vision statement. These vision things inevitably seem to lead to some generic yet draconian expressions (e.g. “to be the pre-eminent” something) that could only be generated by a de-generated consultant brain. Moreover, inevitably they appear to be highly similar to the terminology on the wall of the firm next door. Nevertheless, our senior executives do seem to take them quite seriously. I guess they’re typical of top managers’ efforts and struggle to “align the organisation towards one common goal”; in their desperation they even turn to hammering a mission or vision statement on the canteen’s wall. Guess it really is a struggle.

What struck me about all these three topics, however, is that none of them are decisions. It seems – also from analysing the remainder of our survey – that top managers are quite unfazed by strategic decisions, no matter how big and far-reaching they are. But things they can’t “decree” – like having an effective team, organic growth, or a common vision – is what keeps them awake.

Indeed, you can’t just declare “I decide that next year our organic growth will be 30 percent”. Instead, you will have to build and nurture an organisation which fosters innovation and motivates people and other stakeholders to achieve autonomous growth. You can’t just decide to have it, like you decide to pursue a particular acquisition, enter a new foreign market, or diversify into a new line of business. Similarly, you can’t just decide to attract and retain talent, or decide that “from now on everybody will believe in the same vision and aspiration”. It simply doesn’t work that way. And apparently top managers are a lot more comfortable with stuff they can decide than with things that are not under their direct control; things they need to foster and carefully build up over a longer period of time. And I don’t blame them: that stuff seems easier said than done.

Tuesday, November 4, 2008

How to justify paying top managers too much

Although there is of course a bit of a market at work, it has to be said that the people who determine the pay of a company’s CEO – the board of directors – do face a conflict of interest of sorts. Board memberships are nice jobs to have, in the sense that they are usually rather lucrative gigs and provide a pleasant dosage of power and prestige for those who get them. And – and this is where the conflict of interest arises – it’s mostly the company’s top managers who nominate new board members. In the spirit of “don’t bite the hand that just fed you”, board members may be inclined to nominate their benefactors (i.e. the CEO) handsomely by returning the favour in the form of a nice compensation package.

Moreover, as research has shown, those directors who deviate from this social norm (and for instance vote for a relatively low CEO compensation package) will be frowned upon by the rest of the business elite, spat at and given the cold shoulder until they “come to their senses” and don’t display such ridiculous behaviour any longer.

For this reason, in various countries, boards of directors now have to justify the compensation packages that they give to their CEOs by explicitly comparing the firm and its performance to a “peer group”. The idea is that, due to this forced comparison, it becomes more difficult for boards to step out of line.

The tricky thing is, of course, how do you determine who the company’s peer group is…?

It seems most logical to simply pick a group of firms in the company’s main industry, right? Right… but even firms in one and the same industry are usually not entirely comparable; you have many different types of banks, pharmaceutical companies can be vastly dissimilar, software companies are hardly all alike, and one retailer is not identical to the next one. Therefore, boards have a bit of flexibility regarding who to include in their firm’s “peer group”. And that’s of course a rather inviting opportunity for a bit of old-fashioned manipulation…

Professors Joe Porac, Jim Wade and Tim Pollock analysed the composition of the peer groups chosen by the boards of 280 large American companies. For each peer group, they examined how many firms were in there that were not from the company’s primary industry – thinking that then there just might be something fishy going on. Subsequently, they looked at the financial performance of the peer groups, of the companies in the sample, the performance of each company’s industry and the size of the CEOs’ compensation packages.

They found that boards would usually construct peer groups consisting of firms in the company’s primary industry. On average, there were some 30% of firms in those peer groups that weren’t in a company’s line of business. But, guess what: This figure increased significantly if the firm was performing poorly; then the board would construct a peer group of firms (outside the company’s industry) with quite mediocre performance, to make the firm look better. They did the same thing if everybody in the company’s industry was performing well; then a poorer performing peer group obscured the fact that the good performance of the company was nothing unusual in its industry, again making it look comparatively good.

Finally, boards would compose peer groups that consisted of comparatively poorly performing firms from outside the company’s industry if its CEO received a relatively hefty compensation package; then the seemingly high performance of the firm would come in handy to justify the CEO’s big bucks.

Joe, Jim and Tim concluded “boards selectively define peers in self-protective ways”. Which simply means that they dupe us to pay the buggers too much.

Friday, October 31, 2008

Say what…?! Making strategy made simple

And I thought “What…?!”

What (on earth) might Robert mean with that? I don’t know but I am willing to take a guess. Let’s take the first part: “Bottom-up driven internal experimentation and selection processes”. You have to realise that Robert spent much of his academic life in Intel, studying how they developed strategy. And he found that for instance their big success – microprocessors – wasn’t the result of some planned analytical strategy-making process at all. Instead, Intel’s top management had allowed employees to work on some of their pet projects and technologies that these individuals were very enthusiastic about, but from which is was actually quite unclear if they would ever lead to anything useful (and profitable).

Many of these pet projects failed, some of them became reasonably successful (e.g. a product called EPROMS), but there was one which turned out to be this multi-billion dollar product called microprocessors. That’s the “experimentation” part of Robert’s statement (I think...).

Intel’s management did not only allow for this experimentation stuff to happen, it also made sure that at some point, a choice – i.e. a “selection” – would be made in terms of what (pet) products were going to receive priority and be continued, and which ones were going to get the chop. One such selection mechanism was a complex production capacity allocation formula which determined what was and what was not going to be manufactured. Another element concerned high levels of autonomy for middle managers, which made sure that those things most people thought were important for the future of the company would get done, but the things nobody quite believed in (anymore) would die out…

So that’s the “internal experimentation and selection processes” bit (I think). But what is this “maintaining top driven strategic intent”…?

It would be a mistake to believe that companies – including Intel – can be successful without a clear strategic direction (or “intent”) and can just rely on some bottom-up experimentation stuff. If you have bottom-up experimentation without a clear strategic direction in your organisation, soon you will be all over the place. Hence, although these “experimentation and selection processes” are useful, top management will still need to develop a clear strategic course for the firm, to make sure they’re coherent and going somewhere.

Yet, just having a top-down strategy (without the bottom-up stuff) won’t work either; it will likely make you rigid, myopic and simply unsuccessful. You need the top-down strategic intent to give you direction, but you simultaneously need the bottom-up thing to get you the unpredictable, unforeseeable successes that you really can’t dream up as a lone top dog.

Hence, as Robert said (be is slightly awkwardly), you need both, at the same time.

Tuesday, October 28, 2008

The process of making strategy (or just gibberish?)

And I thought “What…?!”

But the more times I read the sentence, and the more I thought about it, and the more I compared it to the strategy-making processes in the (successful) companies I have seen from up close, it actually started to make sense… (although I acknowledge that I have no confirmation that the interpretation I came up with, of Robert’s gibberish, is actually what he meant with it!)

1) In a strategy-making process “managerial action and cognition are intrinsically intertwined”; what the heck might he mean with that? Well, if I think about the companies I’ve analysed, in pretty much all cases, strategy was not the result of a one-time rational analytical process but there was quite a bit of trail-and-error to it.

The firm, for whatever reason, tries something new – a new product, service or process. Or they simply happen to run it to something by accident. For example, Hornby, when they outsourced production of their model trains to China, added additional detail and quality to their products. That’s the “action”.

Then, the firm receives feedback from the market. In Hornby’s case, for example, sales went up. People in the company then stop, take notice and try to understand what led to the result. People in Hornby, for example, discovered that it was now hobbyists and collectors buying their products, instead of children, and they concluded they were moving out of the toy market into the hobby market; that’s the element of “reflection”.

Subsequently, the decided to deliberately try more of this, and add detail and quality to some of their others products as well, refocus their marketing efforts on adults and see what happened (that’s another action). When they noticed that this campaign was a success, they gradually decided to make this market-shift the basis of their new strategy (another moment of reflection). My guess is that’s what Robert meant, with “action and reflection are intrinsically intertwined”.

2) But what did he mean with it is “a social learning process”…? Well, my guess is that he meant a top manager doesn’t do this all by himself. It involves lots of people in the organisation – which is why it is a social process – and even from outside the firm. Hornby employees debated at length what was causing the surge in their sales, after outsourcing their production to China, and where it came from. They even explicitly involved their retailers in this discussion, to try and understand their view on what had happened to them.

3) Finally, what might Robert have meant with strategy making “in the emergent stage”…? Well, all of this means that strategy isn’t necessarily planned, especially in the beginning; organisations try stuff, some of it fails, other things stick and some of them become big successes. As a result of these processes, strategy happens; it emerges from within a (good and effective) organisation, rather than that it is the result of some 100 percent rational model and process. In later stages, it may become more deliberate and planned, just like Hornby nowadays very carefully taylors its products to hobbyists.

And that’s not only a very realistic view of how strategy really happens, but perhaps also one that a good organisation should aspire to. Because purely rational, planned strategies are seldom the big break-through successes. Simply because life is more complex than that. Just like Robert’s language.

Sunday, October 26, 2008

THE CREDIT CRISIS, VOLATILE MARKETS, RECESSION AND MEDIA

Most media can survive the collapse of credit markets because media firms have high cash flows are typically require less short term credit than manufacturing and retail firms. Because most can acquire their most important resources without accessing credit lines or issuing commercial paper, banks struggling to keep their heads above water are not a major short-term concern. However, those media firms with large debts due in the short-term that were hoping to refinance face significant hurdles. Some will be rapidly shedding media properties in order to stay afloat.

The more immediate problem for some publicly owned firms is the financial damage caused by the dramatic drop in share prices following the credit market collapse. Because a number of companies use debt financing linked to the value of their shares, the drop in prices makes their debt more risky and thus triggers automatic increases in interest rates and debt payments. This puts even more financial pressure on the firms and is sweeping them along with the flood.

Media firms that escaped the rising financial damage of the first two problems are nonetheless being sucked into the swirling waters of a recession. Because manufacturers are cutting production and laying off workers and because credit is tightening and making it harder for consumers to buy, advertising expenditures are eroding rapidly. Further, consumer spending and confidence are directly related to sales of media products so one can expect declines in sales of media hardware, recordings, books, and other products as well as consumers concentrate their expenditures on paying mortgages and other debt.

At the moment there is no means to effectively project how deep the recession will be, but whatever the depth it will be difficult for media. In the case of advertising, a 1 percent decline in GDP produces about a 3 to 5 percent decline in advertising. So a 3 percent decline could produce a 15 percent decline in income for many media firms. Print media tend to be most affected by recessions and their declines tend to be 3 to 4 times deeper than television because of differences in the types of advertising they carry.

Media companies that are financially strong will weather the financial storm, but those whose managers leveraged their companies to make acquisitions, those whose owners recently purchased the firms primarily using debt financing, and those that have been poorly managed will be struggling to survive. The current financial storm is a classic example for why conservative financial management of a media firm debt is crucial.

Thursday, October 23, 2008

Framing something as a threat or an opportunity dramatically alters what we choose

Imagine that the US is preparing for an outbreak of an unusual Asian disease, which is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programmes to combat the disease have been proposed.

Assume that the exact scientific estimates of the consequences of the programmes are as follows:

If programme A is adopted, 200 will be saved.

If programme B is adopted, there is a one-third probability that 600 people will be saved and a two-thirds probability that no people will be saved.

Which one of the two programmes would you prefer?

Kahneman and Tversky found that a substantial majority of people would choose programme A.

Then they gave another group of people the assignment but with the following description of the (same) options:

If programme A is adopted, 400 people will die.

If programme B is adopted, there is a one-third probability that nobody will die and a two-thirds probability that 600 people will die.

They found that, in this case, a clear majority of respondents favoured programme B! But the programmes really are exactly the same in both cases…!? How come people’s preferences flip although they are confronted with the exact same set of choices (be it described slightly differently)?

It is due to what we call “framing effects”, and they greatly affect people’s preferences and decisions. For instance, In the first case, programme A is described in terms of the certainty of surviving (which people like), but in the second case it is described in terms of the certainty of dying (which people don’t like at all!). Therefore, people choose A when confronted with the first programme description, while in the second case they favour B, although the programmes are the same in both situations.

We also see this influence in strategic decision-making, for instance in terms of whether particular environmental developments are “framed” as opportunities (which we like) or threats (which we don’t like). A few years back, Clark Gilbert – at the time a professor at the Harvard Business School – analysed American newspapers’ responses to the rise of on-line media in the mid-1990s.

He found that those newspapers that, in their internal communications and deliberations, described on-line media as an opportunity (e.g. “a new avenue for attracting advertising revenue”) coped quite well. In contrast, those newspapers that framed the exact same technological developments as a threat (e.g. “it will eat into our advertising market share”) didn’t cope very well at all. In light of the threat, they reduced investments in experimentation, adopted a more authoritarian organisation and management style, and focused more narrowly on their existing resources and activities. As a result, they basically ended up copying their physical newspaper onto the web; and that didn’t work at all. Many of them didn’t survive.

And this effect is quite omni-present. How you frame decision-situations to someone (e.g. your boss) is going to influence substantially what option he is going to favour. How the people who work for you frame a situation while presenting to you, is also going to determine what you will choose. And I guess that may be an opportunity (or a threat…) in and of itself.

Tuesday, October 21, 2008

Pay inequality – good or bad for team performance?

This question can stir a fair bit of debate, and I have heard it been argued one way and the other. “You should pay them all the same” some loudly proclaim, “because they’re a team and you don’t want to create envy and inequality within the group!” Others will bellow in agony: “But you need to incentivize people – stupid!; equal pay kills their motivation; you should pay more to people who (seem to) contribute more, to keep them happy while stimulating the others to better themselves!!”.

And who knows whether it is one way or the other. The problem is, it is very difficult to research properly, and find a conclusive and reliable answer. You’d of course need information on the exact remuneration of all people in a team, their individual performance and their team performance, and have a whole bunch of identical teams to make meaningful comparisons. And that’s easier said than done.

Professor Matt Bloom, from the University of Notre Dame, decided to give it a try. And to make sure that he had a clean research sample, with a whole bunch of similar teams doing the same task, for which he could collect all the relevant info, he chose Major League Baseball.

And, although a bit unconventional, that’s perhaps not such a bad idea…! I don’t know much about baseball (and would prefer to keep it that way!) but I assume the rules are the same for everyone, the teams the same size, working on the same task, etc. Thus, Matt collected performance data on 1644 players in 29 teams, assessing their individual performance through batting runs, fielding runs, earned run averages, pitching runs, player ratings and all this (for me) abacadabra. For team performance, he measured a combination of on-field performance and financial performance, using game wins and revenue and valuation data. So, this gave him measures for team performance and the individual performance of each member of the team.

Then he measured player compensation; The newspaper USA Today apparently publishes salary and performance incentives for all players, so he used that. Finally, he created an indicator of “pay dispersion”, or how big are the differences in the levels of pay between the players on a team. Using this data, he computed whether clubs were better off equalising pay, or differentiating their team’s payment levels.

And, so it turned out, it’s the former: that is, baseball teams performed better if the salaries of the players were not too different from each other. The larger the payment differences, the lower the individual players’ performance; mostly so – perhaps not surprisingly – for the players receiving the lowest payment. But – perhaps more surprisingly – also the players who found themselves pretty high in the payment pecking order, receiving an above-avarege salary package, saw their individual performance being negatively affected by the pay dispersion within the team.

Finally, team performance: Those teams with high pay differences among players had markedly poorer performance. It seems substantial differences in pay are more of a de-motivator than an incentive, even for the majority of people who end up in the high payment bracket! And the team suffers from it as a result.

Friday, October 17, 2008

Dirty laundry: Who is hiding the bad stuff?

Some years back, two researchers – Eric Abrahamson from Columbia Business School and Choelsoon Park, at the time at the London Business School – examined this question systematically. Their answer – perhaps not surprisingly – was “yes”.

Fortunately, however, they did not stop there. Because perhaps the more interesting question is, “who is concealing the bad stuff” or, put differently, which firms are inclined to hide their dirty laundry?

Eric and Choelsoon investigated so-called letters to shareholders of 1118 companies as published in these firms’ annual reports. There is quite a bit of evidence that these letters to shareholders form one of the main communication devices of firms to their shareholders and that they have some real impact on companies’ share price. Eric and Choelsoon, through computer analysis of the wording of these letters, made a measure of how much negative information was disclosed in them.

In addition, they collected information on a bunch of other variables, such as the firms’ (subsequent) performance, the percentage of outside directors on their boards, shares held by those outside directors, institutional ownership of the companies, auditor reports, etc. And they uncovered some pretty gritty stuff.

So, their finding number one was: Company Presidents - who formally write these letters - are tempted to lie and hide their company’s bad news. I reckon that is only human. My guess is many of us might be tempted to tone down our failures (and play up our achievements a bit) in such very public statements, to not feel embarrassed and make ourselves look successful. But there are things that can be done, in terms of corporate governance, to stem their & our natural inclination to obscure the truth.

That brings me to finding number two: Eric and Choelsoon showed that having outside directors on the board made firms lie less. The more outside directors firms had the more forthcoming they were with their bad news. Similarly, having large institutional investors prompted firms to be more open about their failures in these letters to shareholders. Large institutional investors tend to monitor the firms they invest in quite closely, which apparently gives them less opportunity to conceal the negative stuff.

But then came finding number three: If we gave our outside directors shares in the company, the results flipped…! Firms that had outside directors who also were quite major shareholders were less forthcoming in disclosing their bad news. It seems that having an ownership stake in the company created a conflict of interest for these people which induced them to stimulate their firm to hide its dirty laundry rather than disclose it.

Moreover, having lots of small institutional investors – who don’t scrutinise companies as strictly – also made the results flip: Firms with lots of small institutional investors hid their bad news more often, probably because they were afraid these investors would run at the slightest hint of bad news (which they are indeed known to do), which could snowball and send the firm’s share price plummeting. To conclude, having outside directors may be a good thing, but only if they don’t have a lot of shares. Institutional investors may be a good thing too, but only if they do have a big stake.

Tuesday, October 14, 2008

"Reverse causality" – sorry, but life's not that simple

They usually follow a simple yet appealing formula. They look at a number of very successful companies, see what they have in common, and then conclude “this must be a good thing!” Yet, reality – and strategy research – is a bit trickier than that.

One conclusion many of these business books draw is that one should focus on a limited set of “core activities”. For example, “Profit from the Core” authors Chris Zook and James Allan find that 78% of the high-performing firms in their sample of 1,854 companies focus on just one set of core activities, while a mere 22% of the low-performing companies did. Hence, they conclude that companies should focus.* Simple isn't it? Yeah, but a bit too simple...

What this “advice” ignores is that often underperforming companies diversify into other businesses in order to try to find markets that are more rewarding for them. Thus, their “non-focus” is the result of poor performance, rather than the cause! In contrast, it’s very common that very successful companies narrow their strategic focus in order to concentrate on the business that brings them most success. Again, their focus is not the cause of their success; it is the result of it. Our best-selling-business-book-friends may be reversing cause and effect; recommending everybody to apply more focus may be dubious advice at best!

Similarly, many of these business books conclude that the high-performing companies they looked at all had very strong and homogeneous corporate cultures. Hence, they conclude: create a strong corporate culture! Seductively simple again... Unfortunately, not so sound.

It is a well-known effect in academic research that success may gradually start to create a homogeneous organisational culture. Again, the coherent culture is not the cause of the company’s success, but the result of it! What’s worse, a narrow, dogmatic corporate culture may be the foreboding of trouble. When the firm’s business environment changes – and all environments eventually do – it makes the company rigid and unable to adapt; a phenomenon known as the success trap.

Indeed, the authors of “In Search of Excellence” – Peters and Waterman – published in 1982, who analysed 43 of "the most excellent companies in the world", also concluded that a strong corporate culture was a necessity for business stardom. However, if you look at their list of 43 "most excellent companies” today, only three or four might still make the list (Johnson & Johnson, Intel, Wal-Mart, Mars); the remainder has gone down or disappeared altogether.

Hence, remember that “association is not causation”. For example, that successful companies are associated with a very focused set of business activities and strong corporate cultures does not mean that this is what caused their success. Importantly, trying to replicate these symptoms of success may actually prevent you from attaining it.

* For more insight into these type of effects, see for instance the work of Stanford Professor Jerker Denrell

Thursday, October 9, 2008

Successful managers – incompetent for sure

So what makes for a good risk manager? Well, it is someone who carefully chooses the best odds. He will sometimes win, and sometimes lose. But, always, he will make quite deliberate and careful trade-offs between his assessment of risk and return; the most expected return for the least risk. Sometimes good managers accept a low return when it is safe (like buying government bonds); sometimes they accept a lot more risk in return for a higher expected return (like investing in the stock market).

Bad managers are those people who just don’t get it. They accept worse average returns for higher risks. And this is where it gets tricky.

Because if they accept very high risks, in spite of lower average returns, every once in a while one of these morons will actually hit the jack-pot…*

That is, if we take the top 1 percent – and only this 1 percent – of top performers, they’re likely to be those people who don’t get it at all… but just got incredibly lucky!

The same is true – as Stanford’s Professor Jim March asserted – for CEOs. The ones that are the eye-catching top-performers are likely the ones who just don’t get it. The dangerous thing is that they are also the ones with the absolute highest return in their business. Therefore we naively believe that they “do get it” and, in fact, are quite brilliant. Moreover, that’s what they start to believe as well… (“I win again; I must be brilliant…!”). Yet, they got lucky once, the might get lucky twice, or three times (at which point we start to notice them) but eventually their luck will turn (the names of Bernard Tapie, Jeff Skilling, Cees van der Hoeven and Conrad Black come to mind).